In December 1941, Japanese forces were poised to sweep down the Malay Peninsula and conquer Singapore, once thought to be an invincible fortress.

LEAD-UP TO THE FALL: In late September 1940, Germany, Italy & Japan signed a pact recognising the right of Axis powers to establish a ‘new order’ in Europe and Japan’s right to establish a ‘New Order of Greater East Asia’. Although this was before Japan was officially engaged in the Second World War, the Allies and America were worried about the Nippon Empire’s expansionary intentions, having witnessed its invasion of Manchuria, China and Korea, among other signs.

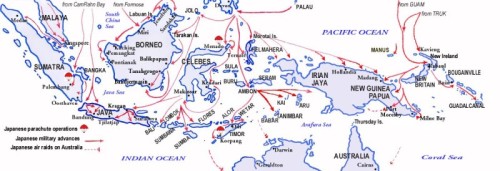

Southeast Asia (Map: Phuket Jet Tour)

During 1941, anxiety by Australia and many Britons increased about the exposed situation of Singapore and the Malay States. Eventually, Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill dispatched his nation’s newest battle- ship, the Prince of Wales, and a cruiser, the Repulse, to the island city, which they reached on 2 December. The Japanese fleet which was to attack Pearl Harbor had already set sail from its homeland a week beforehand, with the Allies unaware of its intent.

In late November 1941, military intelligence from the United States – not yet officially in the war – had warned of an imminent Japanese attack on Siam (Thailand), and in early December the U.S. gave assurance of armed support in the event of Nippon assault on British territory or the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). The Japanese shot down an Allied plane over Southeast Asian waters, but still the British refrained from retaliatory action. Then, without warning, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on the morning of 7 December, with devastating effect.

ADVANCE THROUGH MALAYA: While American facilities were still smouldering that night, the first of 17,000 Nippon troops landed at positions near the Siam/Malaya border, while air raids on Singapore began the following dawn. It had been assumed that attack would come from the sea, so Singapore’s guns were pointed that way. As Churchill wrote later: “It never occurred to me that… the fortress of Singapore… was not entirely fortified against an attack from northward.” Instead, the Japanese swept down through through the Malay peninsula. One key mode of transport: bicycles!

The Japanese already had a considerable naval presence in the area, so the British “Force Z” embarked with the plan of engaging enemy craft in the South China Sea. This fleet consisted of the Prince of Wales, Repulse and four destroyers but lacked sufficient air support, which the Nips had aplenty. As the fleet headed for Kuantan on Malaya’s east coast two days later, it was attacked from the air and hit by torpedo bombs. Repulse was first to sink and Prince of Wales followed. All up, 840 Force Z personnel perished.

The Prince of Wales sinking

Winston Churchill recorded later: “In all the war, I never received a more direct shock… the full horror sank in… in the Indian Ocean or the Pacific… Japan was supreme, and we everywhere were weak and naked.”

British and Australian troops and local militia put up a desperate defence in Malaya, but in the end were no match for the invaders. By the end of January, Allied forces had withdrawn across a narrow causeway to Singapore. While the Nips were sweeping down Malaya and even as they were vanquishing Singapore city, all kinds of people escaped or attempted to escape, mainly via the harbour, in all sorts of craft. Meantime, Japanese air and sea power had reached the area and put paid to many such efforts. Luckier ones made it either to the Indian Ocean or to the large islands of Sumatra or Java, in the Dutch East Indies.

INVASION OF SINGAPORE: On 8 February, Nippon troops crossed onto Singapore Island and a week later were at the outskirts of the city, which was heavily bombarded, with dreadful civilian casualties. Evacuations by all manner of means, which had begun the previous month, were desperately stepped up.

However, by 15 February the British commander of Singapore, Lt. General Percival, bowed to the inevitable and surrendered. Incarceration of tens of thousands of Allied troops and civilians followed, as well as the outright slaughter of thousands of Chinese and Indians.

Of the 15,000 Aussies taken prisoner, a third had died by the end of the Pacific War in August 1945; the attrition rate for British POWs was even higher. Among the British troops were many Indians, as the sub-continent was then still colonised by Britain. It is a very sobering thing to walk among the gravestones of Changi Prison (as I’ve done) and read the ages of these victims, so many of them just plus or minus twenty years old.

British brass at the surrender (Percival far right)

British brass at the surrender (Percival far right)

Churchill was deeply affected by the fall of Singapore, though the only responsibility he would openly take was in a remark he made later about the island’s vulnerability to land attack: “Somebody should have told me sooner, and I should have asked.”

Good short YouTube videos: “WWII Fall of Singapore 1941” & “Japanese Occupation of Singapore” (among others).

SELECT SOURCES:

Carlton M, 2010, Cruiser, Hienemann, Sydney.

Charlton C, 1988, War Against Japan, Dreamweaver, Sydney.

Corfield J & Corfield R, 2012, The Fall of Singapore, Hardie Grant, Melbourne.

Ewer P, 2013, The Long Road to Changi, ABC Books, Sydney.

Holder R, 2007, The Fight for Malaya, Editions Didier Millet, Kuala Lumpur.

Lewis G, 1991, Out East in the Malay Peninsula, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia.

Marston D (ed), 2005, The Pacific War Companion, Osprey, Oxford.

McCormac C, 1954, You’ll Die in Singapore, Robert Hale, London.

Moremon J, 2002, A Bitter Fate, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

Morrison I, 1993, Malayan Postscript, S. Abdul Majeed, Kuala Lumpur.

Shennan M, 2000, Out in the Midday Sun, John Murray, London.

Shinozaki M, 1975, Syonan – My Story, Times Books International, Singapore.

Thompson P, 2008, Pacific Fury, Hienemann, Sydney.

Warren, A. 2002, Singapore 1942: Britain’s Great Defeat, Talisman, Sydney.

Weller G, 1943, Singapore is Silent, Harcourt, Brace & Co, New York.

Wyett J, 1996, Staff Wallah at the Fall of Singapore, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards.

For info on the invasion of the Dutch East Indies, see my post “Japanese Invasion of Java“.

The former Dutch East Indies are the setting for my novel, Shadow Chase, out now. Check it out at http://www.shadow-chase.com, where you can find other material related to Indonesia.

The former Dutch East Indies are the setting for my novel, Shadow Chase, out now. Check it out at http://www.shadow-chase.com, where you can find other material related to Indonesia.

The prompt for this reverie about Malang is that right now marks (unbelievably, for me) twenty years since I went to live there. It was my first time to relocate abroad & my first teaching post, at Merdeka University. I was over forty and the move marked a sea-change in my life, when I made the great leap to another country and another culture. Below is the complex for the hospitality course where I taught – and lived, for a short while, in a room at the back of these buildings.

The prompt for this reverie about Malang is that right now marks (unbelievably, for me) twenty years since I went to live there. It was my first time to relocate abroad & my first teaching post, at Merdeka University. I was over forty and the move marked a sea-change in my life, when I made the great leap to another country and another culture. Below is the complex for the hospitality course where I taught – and lived, for a short while, in a room at the back of these buildings. Javanese/Madurese, very rural, very traditional. In the more remote villages, you can still find a scene of bullock-drawn carts, fence-less housing compounds, shared ablutions at the communal well or water-trough, and a very close sense of community.

Javanese/Madurese, very rural, very traditional. In the more remote villages, you can still find a scene of bullock-drawn carts, fence-less housing compounds, shared ablutions at the communal well or water-trough, and a very close sense of community. East Java in the late 1940s forms the setting for a major strand of my novel, Shadow Chase. Check it out at http://www.shadow-chase.com, where you can also find other material related to Indonesia.

East Java in the late 1940s forms the setting for a major strand of my novel, Shadow Chase. Check it out at http://www.shadow-chase.com, where you can also find other material related to Indonesia.